Crudo Volta & Python Syndicate

Crudo Volta is a collective at the forefront of contemporary African music, producing cutting-edge documentaries, with a sub-label called Python Syndicate serving as a channel for music production. To learn more about this fascinating platform, we spoke to Mikael Calandra Achode, the mastermind behind the whole adventure!

Mike has had a lot going on in the past 5 years, in between designing work and teaching, he met major success with Crudo Volta’s critically acclaimed documentaries Woza Taxi (briefly introduced in our interview with Francesco Cucchi) and Yenkyi Taxi:

But let’s take it backwards and start with the latest! The Python Syndicate label just released a capsule collaboration of music & fashion with Ghanaian street wear brand Free the Youth. Titled Free Borga, after the distinctive style emerging from Ghanaian highlife musicians moving to Europe or the USA in the 1980s, the collab’ features a great 8 tracks compilation, Heaven’s Gate No Bribe (another nod to Ghana, where you would see this kind of religious messages at the back of every taxis & buses).

"The connection came through Chris Adofo, a collaborator with Crudo Volta who is currently writing a book on Afrobeats. He was in Accra last December and met this collective of young creators, with positive representation", Mike explained.

"We organized screenings of our work with them and the idea of a capsule came up, with music attached to it, showcasing the African diaspora's creativity".

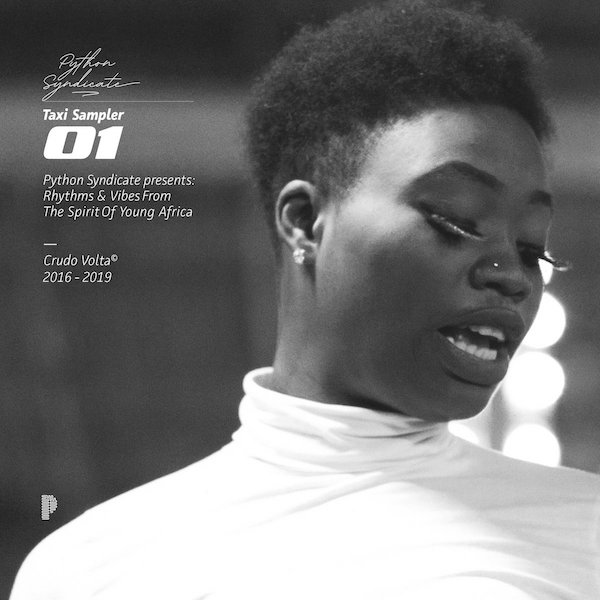

KaySo, featured on Free Borga

8 artists are featured, representing a wide array of sonic experiments from West Africa, London or L.A, blending R&B, Afrohouse, UK Funky, or Dancehall with more classic styles like Highlife and Afrobeat, making the ensemble difficult to pinpoint, yet boiling!

"It wouldn’t make sense to limit the releases to a genre, or try to label our music too much", Mike says. Africans have a polychromic patchwork approach to things, much like in the polyrhythmic percussive tradition, where drums interact with each other even though laying different rhythms. And our aim with these compilations is to showcase a feeling, an aesthetic of the mind, of what it means to be African right now"!

"That’s our contribution to the scene, sharing, pushing, spreading that FEELING that can’t otherwise be put in written words".

KG, featured on Free Borga

Free Borga follows-up after a 1st amazing release titled Taxi Sampler, which came after the filiming of Crudo Volta’s Taxi Series of documentaries: Woza Taxi, Yenki Taxi, and Taxi Waves, filmed in Durban (South Africa), Accra (Ghana), Lagos (Nigeria), Addis Abeba (Ethiopia) and Maputo (Mozambique). The vinyl release came with a beautiful 26 pages booklet, and featured an incredibly large spectrum of contemporary African beats .

"We met so many incredible talents while filming in these different locations", Mike told me, "so we thought it would make sense to link-up and promote their music. With retrospect, I’m amazed to see how many musicians we filmed, or produced on the compilation, became pivotal on the emerging African scene". Indeed artists like** Gafacci, Rvdical the Kid, Ethiopian Records, Sess the Problem, or **Citizen Boy for instance, are all now key players of the forward-thinking beats scene across the continent.

Interview

Tell me a little bit about the inception of Crudo Volta, how did the whole concept come about?

So, there are different timelines in the experience and several factors that drove me to it: I was born in Benin but lived around Europe most of my adult life, and a few years back, after making music in Italy for about 12 years (producing Hip-Hop and Dancehall), I found myself unhappy about my creative journey. I was very much influenced by music from the US and Jamaica, and I felt like my approach was gimmicky instead of actually coming from my feelings. Something was missing, something I call the Black element, which I eventually found when I moved to London and got closer to a Black/African community, where I felt my skills improved. It’s from a sort of an aesthetic of the mind, present in the community, and music is used as a language to convey certain feelings.

Around the same time I became a dad and felt I needed a proper job, and as I’m also passionate about visual art, I started studying and working in graphic design. It made me reflect a lot on the impact of the profession in society, the impact of image. It was around the period of the “Arab Spring” and the major turmoil that followed, including the ensuing big media focus on African migrants. You know, we have very short-term memory, but the imaginary of Africa in the West was very different 10 years ago. And we started seeing these images reinforcing the idea of a poor, destabilized Africa, and very negative and diminishing images of African migrants.

This was before the current socio-economic conversation, and the push for representation of so called “minorities” or marginalized communities. It made me think that my wanting to have a corporate job may push me to take part in something I was criticizing, selling and translating ideas visually, or representations that I found problematic. So I wondered, as an African, an immigrant, how could I take part in economies connected to my roots, rather than nurturing conflicting ones?

But before even considering participating in African or Pan-African economies, I went through some soul searching and wanted to understand what it is to be African.

At the time, even among African communities, the diaspora, and Afro-centrists spheres trying to deconstruct the colonial discourse, there was a lot of space for reminding of Africa’s glorious past, its mighty kingdoms etc., mixed with a growing sentiment that “Africa is the Future” – but there was no discussion about the present! What does it mean or feel like to be African today?

I thought the only way to capture this “Now” was to look into the young demographics, and I started exploring the social media spheres in Africa. I was also convinced that music is the main literature, the key method of cultural archiving and cultural preservation in Africa.

I had produced fanzines before and had a very canonical approach, but started realizing that everyone was increasingly on their smartphones, and it was time to switch to new formats.

Then I met Tomasso Cassinis through one of my best friends. At the time he was filming advertising and editorial stuff for agencies like Magnum and others. He had no experience in documentary making so he was a bit puzzled when I pitched the idea. Essentially I told him: “I want you to follow me around Africa, you know how to use a camera, so let’s go!”

Why did you decide on Morocco as your first destination?

Before anything else, I’m a music digger. I always do a lot of digging around before hitting a country and I always continue after!

At that time (2015), I came across the story of the legendary label and shop Disques GAM in Casablanca, and I was super interested in the Gnawa sound. There was also a wide ranging West African touch in the 1960’s and 70’s, and I also discovered amazing Berber and Jewish music.

I was also keen on filming in a predominantly Muslim country to counter the super negative treatment of African Islam at the time. Most information was heavily focused on the emergence of the so-called Islamic State, Wahabbism etc.. Again, you have to remember that the post-colonial treatment of Africa in the media was much harsher at the time. So I thought it would be interesting to approach the relationship between Maghreb and West Africa, the intricate conversations going on with Mauritanian tribes, Tuaregs, Peuls (Fula people), or Hausas.

That first shoot was meant to revolve around my music digging and discussions with local youth. Not knowing better at the time, I envisioned it somewhat similar to skateboard videos or immersive, gonzo media styles that were emerging then (Vice/ Noisey...). It was a foggy and experimental vision, There was no storyboard of narrative plot. I needed to experiment to find out how I could say what I wanted to say using a contemporary language and a stealth approach.

But then we got there and another format showed up naturally!

So that’s how the taxi format came about?

It came about when we visited those 3 cities in Morocco (Casablanca, Fez, and Rabbat). I realized neither Tommasso nor myself were relating with the skateboard esthetics – it just wasn’t us. We ended up moving about in local “Petit Taxis” and loved the idea as a format: not fully immersed in the local context, a bit like tourists or observers, but engaging in fascinating conversations, hearing stories, talking politics etc.

What was incredible is that when we then headed to Durban for the shooting of “Woza Taxi”, we realized that taxis were the main introduction and promotion points for Gqom !

How did things take off from there? And how did you organize the following filmings?

“Petit Taxi” ended up being a pilot only, which we used as a trailer for a mixtape I was working on. At the time we had the idea to build a radio with Italy as a targeted audience (hence the name Crudo Volta Radio).

That pilot gave me great introduction material to present my vision of driving a better representation of African Culture through contemporary music.

I met Francesco Cucchi (pictured with Mike below) through common friends in Rome, and he was just getting some attention around the first Gqom Oh EP. I thought this would be a perfect match, and the audience for that music in the West needed to see who was behind it, have a proper introduction to these unique artists. Although contemporary African music is accessible and trendy now, at that time (not so long ago) it was not yet officially cool worldwide!

Francesco already had lots of contacts in Durban, all I had to do was convince him and find funds – which I eventually borrowed from my sister!

We started working on the documentary as soon as the first Gqom Oh LP was released, and prepared the whole thing in just 2 weeks.

Woza Taxi (2017) garnered a lot of attention for something produced out of my bedroom! We got tons of coverage from The Fader, Mixmag, Fact, etc.. and the documentary resonated well with white/ European audiences. It also worked quite well in South Africa where Gqom was completely dismissed from the main players. I was happy that it was so accessible and pivotal for the featured artists, who needed representation.

Then Yenkyi Taxi (2018) came from meeting Hagan (pictured above), whom we followed around Accra. There we became familiar with artists like Gafacci and Rvdical the Kid among many. We really explored the connections between modern UK electronic music and West African heritage, and I think the connection with sounds like UK-Funky and the London scene opened the doors to a Black audience, to the diaspora.

It’s also the project I am the most attached to so far – where I felt like I became a Director. All shots, color codes etc. were planned ahead, and we worked a lot on location scouting. I also learned to edit properly.

For me, this second documentary had to be the work of maturity, a real confirmation after the success of Woza Taxi.

I had already received an offer from an Italian streaming platform but I put that on hold as this one was too personal. I wanted to keep room for creative experimentation and avoid loosing focus to satisfy the mainstream!

It was again a major success and we got a lot of good reviews.

The Taxi Waves (2019) sessions were then commissioned by TIMVision, a VOD platform owned by Italia Telecom. They were interested in contemporary African music and gave us a nice budget so we hired local fixers to help us.

In Addis Abeba we got help from people at Afro FM, who introduced us to Rohpan and Ethiopian Records. In Lagos we were supported by Cool FM, and in Mozambique we were driven by Bulldozer, a popular artist from the Pandza scene in Maputo.

Film festivals will be the natural follow-up. We participated to a few so far but have been trying to take it slow while we develop the right image we want to push.

So now, what’s next?

We’re working on the next featured length, but of course everything is on hold with the sanitary crisis.

There’s also an album in the works with Hagan, with major collaboration, but I can’t reveal too much yet… watch this space!

/